Why a Close Campaign Is Good for the Environment

In November, New York will experience an all-too-rare event: a closely contested state senate race.

Just 18 votes (out of 126,408 cast) lifted Democrat Cecelia Tkaczyk above Republican George Amedore in 2012 – ironically in a new district that had been specially designed to give Mr. Amedore the win.

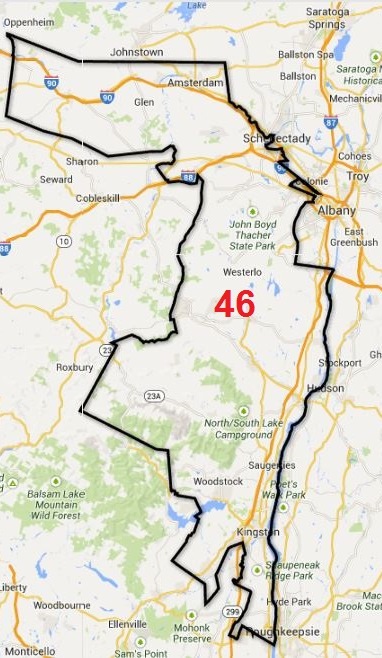

The bizarre state senate district 46 – stretching from the Mohawk Valley to the lower Hudson Valley – was designed in 2012 to ensure victory for a specific candidate

Photo credit: Ballotpedia.com

District gerrymandering is as old as American politics, and it’s really bad for the environment. Gerrymandering typically solidifies districts for a given party, which makes them non-competitive and allows elected officials to overlook their constituents' concerns – because they’ve got the next election sewn up. This decreases the power of grassroots advocates, such as environmental organizations that don’t have the resources to make big campaign contributions. I’ve seen many, many good bills die because safe and secure political representatives didn't bother with the environmental concerns of their constituents, no matter how strong or loud the support.

When districts are competitive (despite gerrymandering), elected officials have to worry about every vote. This gives leverage to grassroots advocates who are representing constituents, and weakens powerful donors representing particular businesses or industries.

So even though Ms. Tkaczyk has a much stronger environmental voting record in the Senate than Mr. Amedore did when he was in the state Assembly, I’m glad it will be a competitive race. If more races were, our environment – and in turn all of us – would be much better off.

[November 7, 2014 update: Mr. Amedore defeated Ms. Tkaczyk in their mid-term race, 50,698 to 39,501.]